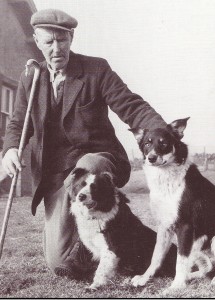

LISTENING to Willie Scott sing The Kielder Hunt, finishing up with that inimitable falsetto whoop, one was conscious of a sough of Cheviot air and the echoes of an older, wilder Border country. One of a long line of Border shepherds and tradition bearers, Willie was a tall, rangy and latterly silver-haired figure with an immense natural dignity, whose store of songs was partly drawn from family, partly from the ballad-haunted landscapes of Yarrow, Ettrick and Liddesdale amid which he spent much of his 60-year working life.

A man who crafted his song performance as carefully as he shaped the shepherds’ crooks for which he was also famed, he used to declare: “A song’s no worth nothing to anybody unless it’s expressed – it’s the feeling and the expression that makes the song.”

As a source singer and bearer of Border traditions, he was highly important. “Willie bridged the old world with the new,” writes Alison McMorland, herself a widely respected ballad singer, who worked with Willie on the invaluable book Herd Laddie of the Glen: Songs of a Border Shepherd, first privately published in 1988 (with proceeds going to the School of Scottish Studies) then revised and republished by Scottish Borders Council in 2007.

Willie’s singing, she continues, at “hill pairties” and herd suppers, Burns Nights and Border kirns among his own working community, was unrecognised outwith it, until the School of Scottish Studies first recorded him in the 1950s. “From then on he reached wider recognition and in retirement was to make an indelible mark on the Scottish scene, singing at festivals and clubs throughout Scotland and England.” Further afield as well, as he sang in Australia with his son, Sandy, and Jean Redpath took him to the United States.

So far as the outside world was concerned, he was first “discovered” by Francis Collinson in 1950, when the musicologist was making his first song-collecting foray into the Border country on behalf of the newly established School of Scottish Studies at Edinburgh University. He had known the area since childhood but had never come across any folk song, just button accordion music. Having been introduced to Willie, who was working at that time at Hartwoodmyres, in the heart of the old Etttrick Forest, he found himself recording a revelatory stream of songs, starting, perhaps appropriately, with The Shepherd’s Song, which was more or less a resume of life as lived by Willie and generations of his kind.

Willie came out with more and more songs, including another favourite of his, Sweet Copshawholm (the old name for Newcastleton in Liddesdale), Irthing Water Foxhounds and that memorable Kielder Hunt. Collinson enjoyed many more recording sessions with Willie, and regarded him as “a major contributor to our present day knowledge of the songs and lore of the Borders.” He recalled being particularly astonished to hear the shepherd come out with “two verses and the tune of the Border riding air Jamie Telfer of the Fair Dodhead … I never expected this to turn up at such a late date, and I will always regret that it did not fall to me to record it.”

Willie was born in 1897 at St Andrew’s Knowes, just a handful of miles from the Border. Both his parents were singers and it was from his mother that he learned some of his most popular songs such as Jamie Raeburn and the Tinkler’s Waddin, as well as that Jamie Telfer fragment. The family moved with his father’s shepherding placements, including Brampton just south of the Border, Gideonscleuch in Teviothead and other often remote Border farms. Attending a handful of schools, where sometimes an enlightened dominie might lead song sessions including the likes of Lock the Door Lariston or Scots Wha Hae, at home he enjoyed “visitations”, where other shepherding families might visit, with many a song shared.

Leaving school when he was almost 12, he took up a herd’s job in Teviotdale. In 1917 he married Frances Thompson and moved to Dryhope in the Yarrow valley, where the first of their six children was born. His career as a shepherd would range through Liddesdale and Ettrick, as well as spells latterly in Fife and on the East Lothian-Berwickshire border, before he retired to Hawick in 1968.

By then, however, he had become renowned on the folk scene for his authoritative delivery, his unique repertoire and droll humour. Hamish Henderson wrote about Willie, at that time working near Kelty, appearing at the inaugural meeting of the Howff Folk Song Club in Dunfermline in 1961. Many of those present had no idea what to expect, but Willie, his performance skills honed by innumerable herds’ suppers and Liddesdale kirns, had the profound impact that he made at so many other folk clubs and festivals. “At Dunfermline,” Henderson recalled, “the world of John Leyden and James Hogg seemed to communicate directly with the new, cosmopolitan folk audience of industrial Scotland through the lips and personality of this masterly veteran tradition bearer.”

As McMorland points out, it was often a two-way process, with Willie giving songs but also learning new ones, as he did with Hamish Henderson’s The Gillie Mhor, and Callieburn, which he got from Willie Mitchell of Campbeltown at an early Blairgowrie festival. “I always felt,” she writes, “that he was a grandfather to the revival, dependable and to be trusted.”

Willie’s musicality has carried on through his children and grandchildren, not least his grandson, Lindsay Scott, a champion Scottish fiddler at the age of 15 and a reminder that Willie himself could be seen with a fiddle tucked in his elbow. Lindsay, who went on to play with the JSD Band, was described by Hamish Henderson as “one of the wild rovers of the Revival”, living in South Africa and elsewhere for many years before returning to Scotland, where he presented music programmes on radio.

Commenting on Willie Scott’s legacy, McMorland points to one of the songs he inherited from his mother, the hugely poignant, Time Wears Awa, which Alison sang at his funeral and which other, younger singers have taken up since. “Apparently he very rarely sang it in public because people wanted the hunting songs and shepherd songs. Without Willie and I working on the book, it would have disappeared, as no-one else, Hamish Henderson or Francis Collinson, recorded him singing it.”

There were several such lesser exposed songs in his repertoire – Pulling Hard Against the Stream, which Alison has also sung, being another.

Working on the book, she continued, “I revelled on the authenticity and no nonsense of his telling and singing. It put me in touch with the old world being brought forward into the light – the long lineage of people, shepherds, their wives and families singing and expressing themselves against the hardships of their existence.”

And she quotes that earlier celebrated Border shepherd, James Hogg, also a song collector, observing that “but for the shepherds at their ingleneuks singing their songs, they would have disappeared”.

Written by Jim Gilchrist 2015